Lumination

-

![]() Aaron Bobrow

Aaron Bobrow

Officer,2014

Sunbrella canvas, vinyl

203.2 x 182.9 cm -

![]() Philippe Roessle

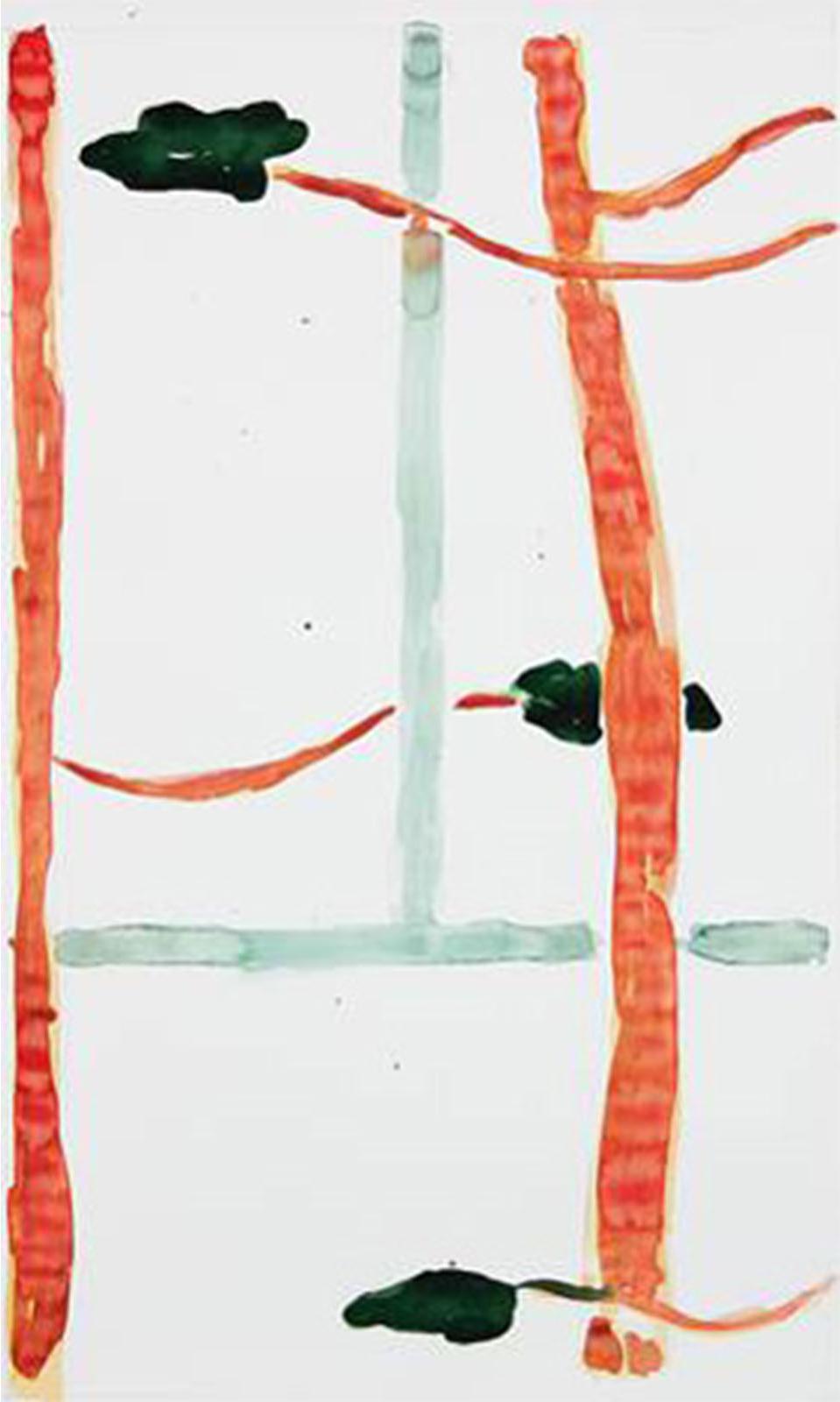

Philippe Roessle

Untitled,2014

Watercolor on paper

100 x 60 cm -

![]() Svenja Deininger

Svenja Deininger

Untitled,2014

Oil on canvas

190 x 130 cm -

![]() Louis Cane

Louis Cane

Toile découpée,1972-1974

Oil on canvas

202 x 273 cm -

![]() Wolfgang Tillmans

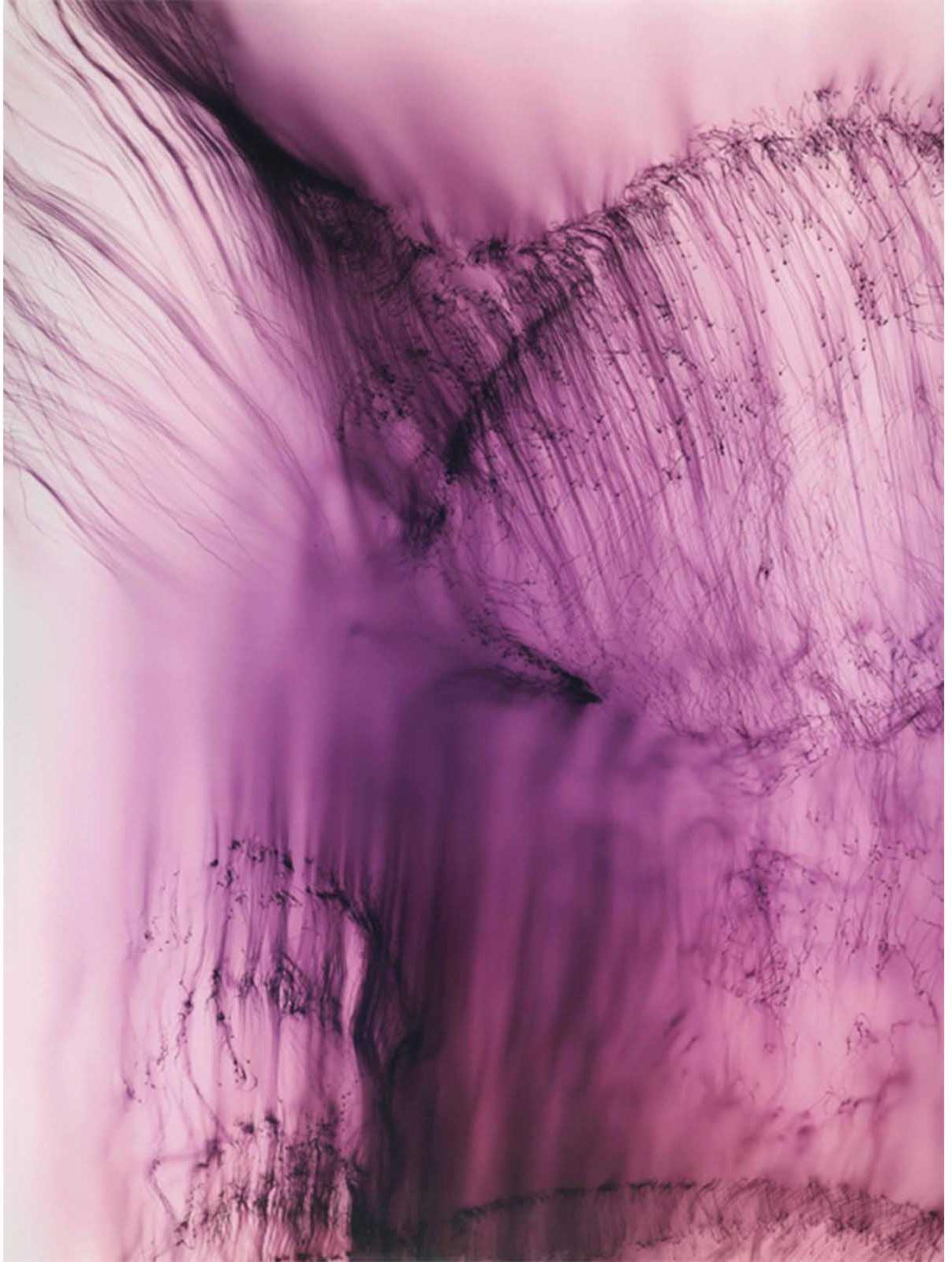

Wolfgang Tillmans

Freischschwimmer,2004

Paper collage print

256 x 195 x 14 cm -

![]() Jean-Baptiste Bernadet

Jean-Baptiste Bernadet

Untitled (Fugue LV),2014

Oil and cold wax on canvas

200 x 180 cm -

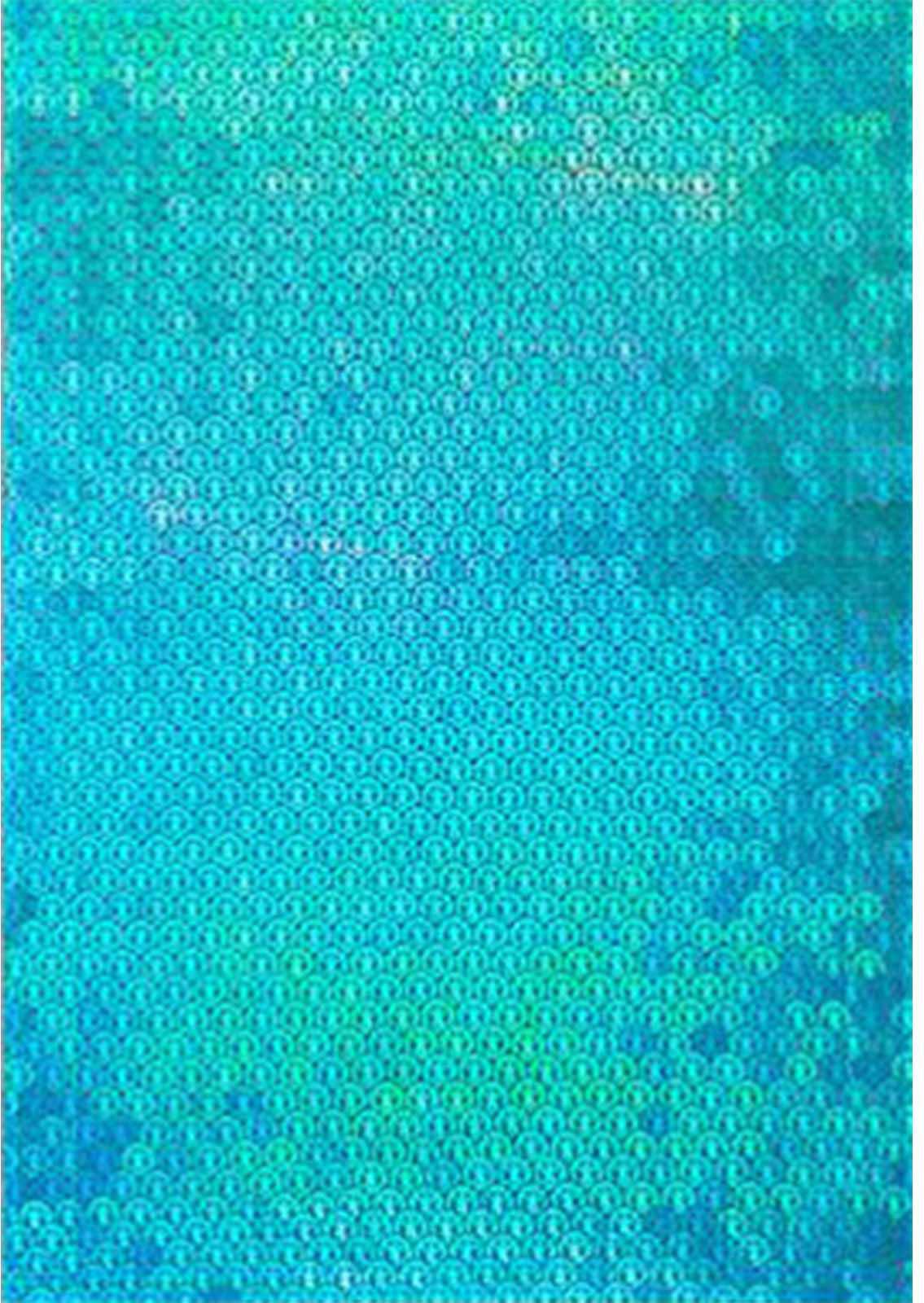

![]() Olivier Laric

Olivier Laric

Inukshuk tribal,2015

Tamper evident security hologram stickers on acrylic, clear coating

139.7 x 99 cm -

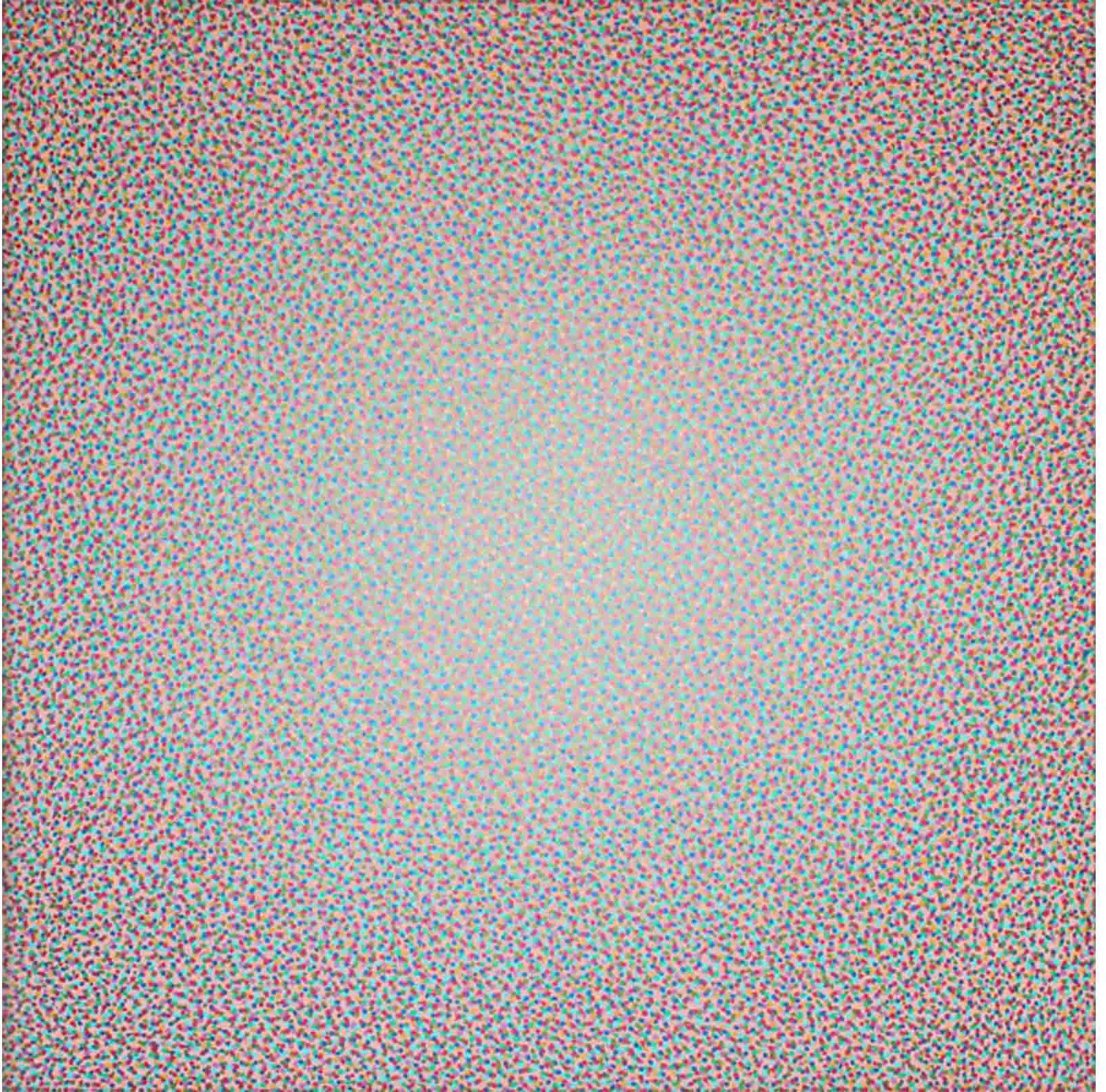

![]() Sally Hazelet-Drummond

Sally Hazelet-Drummond

Untitled,2005

Oil on canvas

45.7 x 45.7 cm -

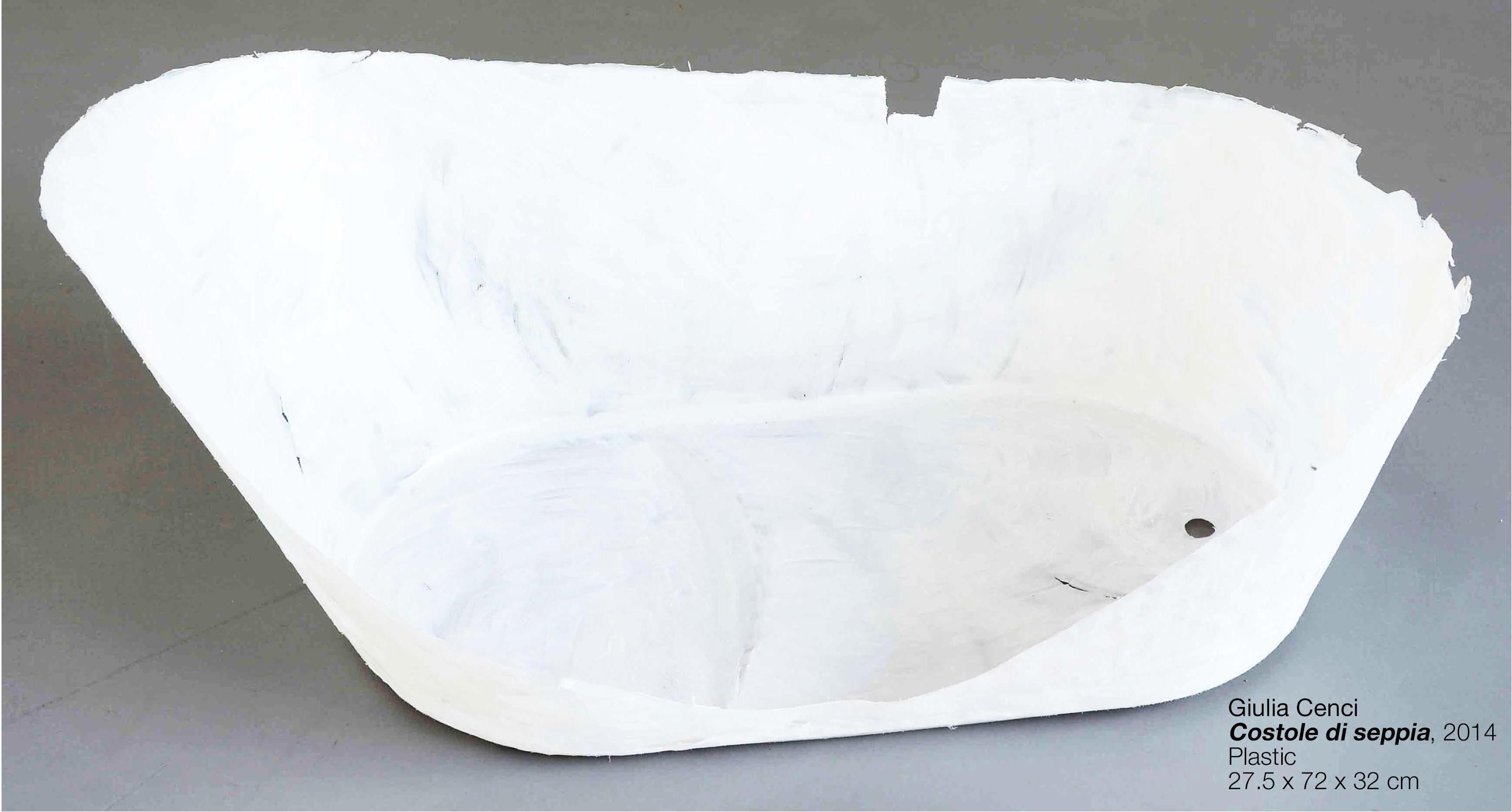

![]() Giulia Cenci

Giulia Cenci

Costole di seppia,2014

Plastic

27.5 x 72 x 32 cm -

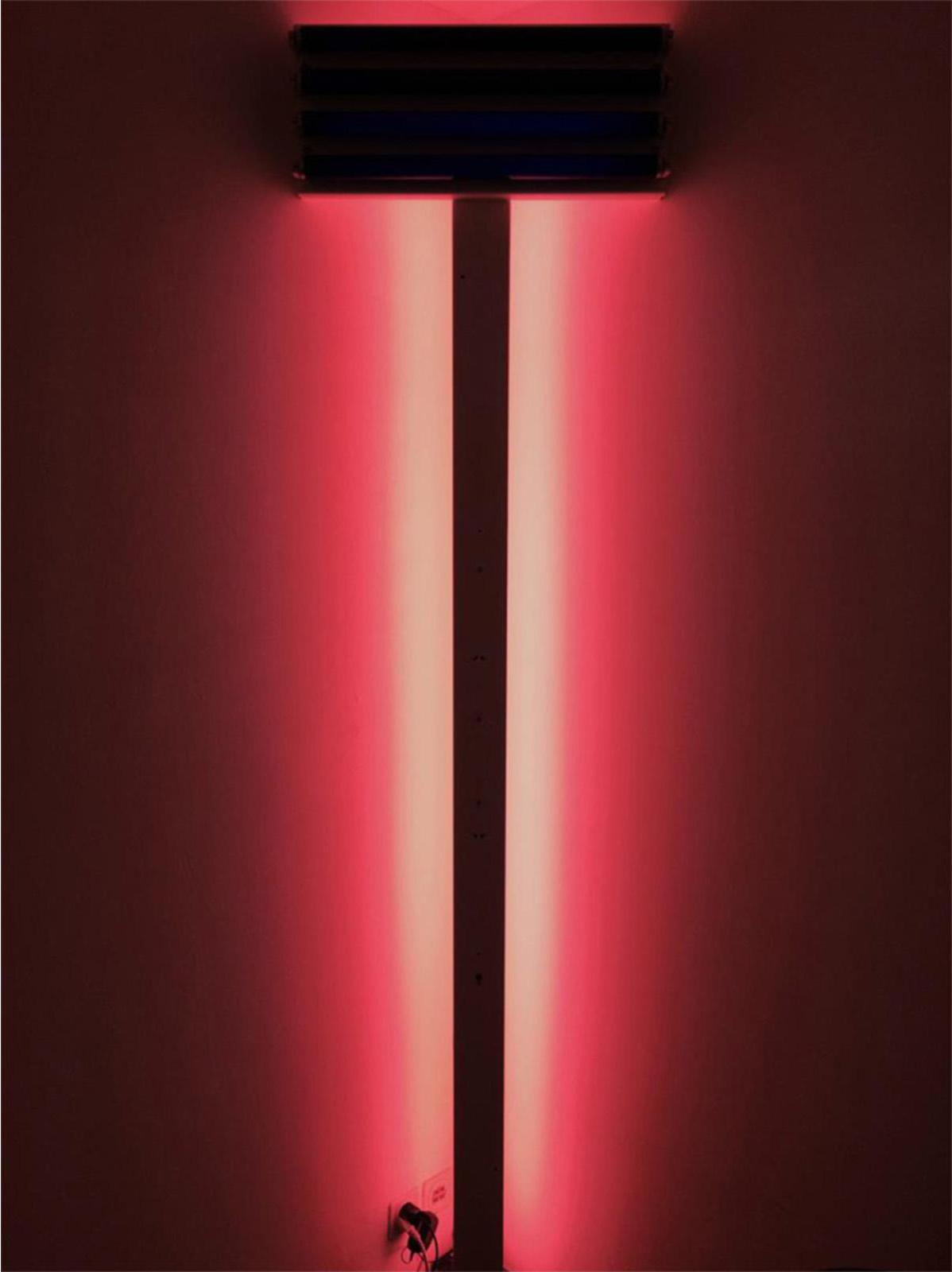

![]() Dan Flavin

Dan Flavin

Untitled (for Prudence and her new baby),1992

Ultraviolet and pink fluorescent lights

243.8 x 61 cm -

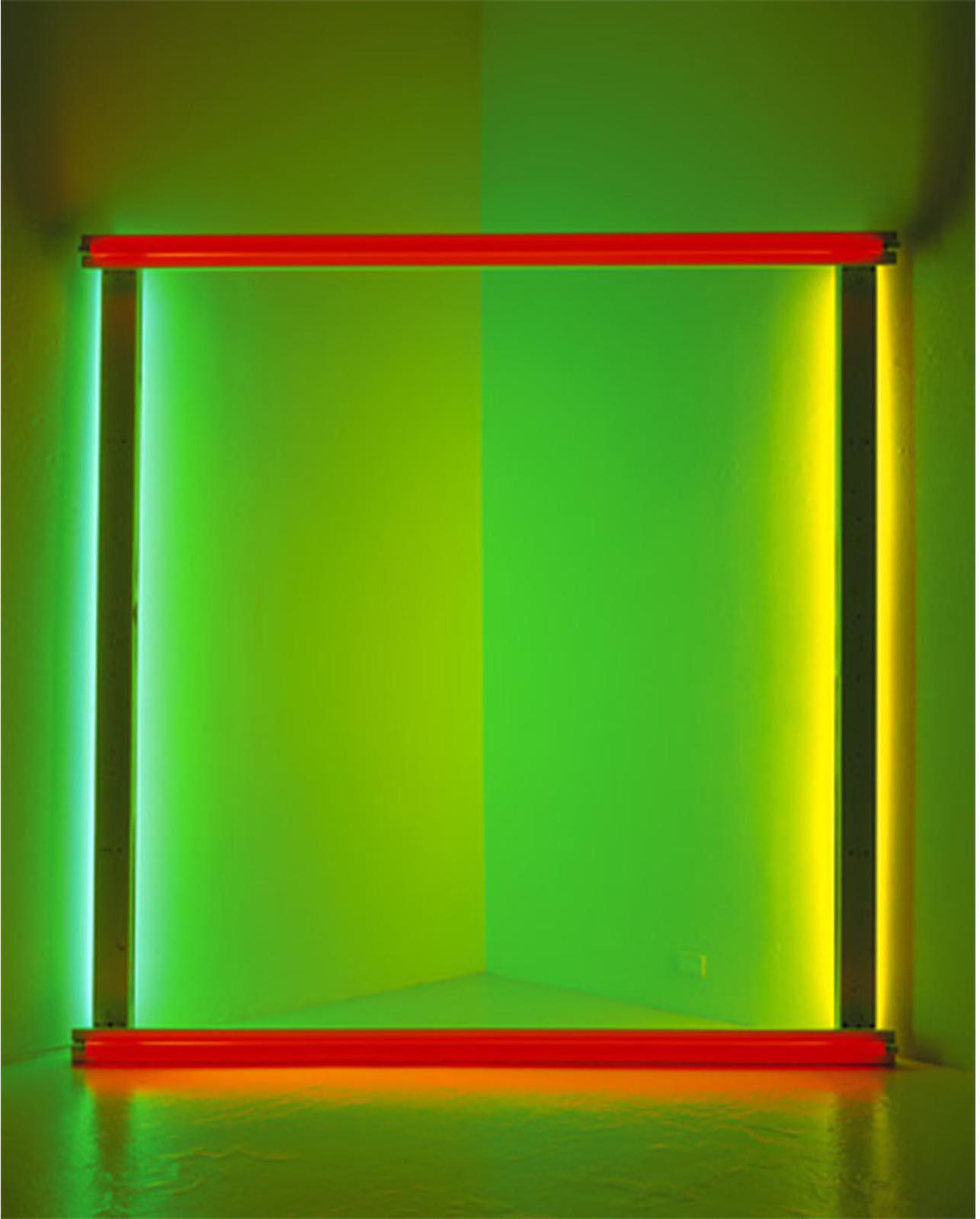

![]() Dan Flavin

Dan Flavin

Untitled (to Bob and Pat Rohm),1969

Red

243.8 x 243.8 x 22.9 cm

Patricia Low Contemporary is excited to present Lumination, an exhibition that explores how artists from the 1960s to the present have used and referred to various technological forms of light, spanning commercial light fixtures to paint-on-canvas to photographic means, to manifest the intense ambiguities and ambivalences of light as a simultaneously physical and ephemeral entity.

The term ‘lumination’ underscores the concerns of the artists in this exhibition with the complex and hard-to-pin-down nature of light as, in certain cases, a kind of quantifiable material; and, in others, an illusory effect. In a recent essay art historian Richard Shiff discusses this in relation to the work of one of the exhibition’s key artists, Dan Flavin:

‘Without the customary directional indicator (il-) the various applications of the concept of lumination weaken the distinction between subject and object, active cause (to luminate) and passive effect (also to luminate, tantamount to being luminated). Flavin’s light has neither object nor objective. It merely lights, like an eye that sees without insisting on a point of view or establishing an organizing perspective. Flavin’s light happens.’

Far from an exhaustive survey, key historical works by Dan Flavin, Jules Olitski, Sally Hazelet Drummond, and Louis Cane anchor the exhibition in several selective, yet seminal legacies extending from the ‘60s and ‘70s.

By examining industrially produced light, Flavin’s work suggests a materialist perspective. While Jules Olitski’s approach, using the more traditional vehicle of paint-on-canvas, can be seen as advancing a painterly color field approach to generating an immersive plane of light. Yet their strategies have certain parallels, if not at the level of materials and presentation, for both artists sought to evoke the sensation of color suspended in the atmosphere. For Olitski this was achieved via his signature use of the spray gun to lay down luminous layers of acrylic. While for Flavin this is the very condition of the chemical reaction by which his fluorescent tubes generate light.

Lumination is framed by these two philosophical and formal poles: between the evocation of light ‘directly’ via light-generating technologies, such as Flavin’s fluorescent tubes; and its suggestion by other means, most expressly through paint. Technological developments in lighting are both inspired by supposedly ‘natural’ experiences of light, and in turn intervene in, and in doing so change, our notions of what ‘natural light’ is. Technology informs life, and vice versa, while art takes note. This has been true at least since Impressionism, when the rapid development of electric light radically changed both the presentation and perception of that favorite Impressionist subject—modern urban life.

It is not surprising, then, that certain artists have periodically returned to the formal, painterly innovations of the Impressionists and their even more scientifically-oriented successors, the Post-Impressionists. The legacy of Seurat’s regular, atomized brushstroke resounds in the work of Sally Hazelet Drummond, a peer of Flavin’s, along whose side she was championed, early in her career, by key Minimalist Donald Judd. Her paintings show the potential for oil on canvas to evoke luminous associations not necessarily found in nature, but which nonetheless don’t feel opposed to the natural.

Louis Cane, a central member of the postwar French association Supports/Surfaces, uses commercial painting procedures—like Olitski, the spray gun, but to very different ends—and an emphasis on materials, lengths of unstretched painted canvas extending in modular panels from ceiling to floor, or presented as an open frame exposing the ground and support behind. All of this is to underscore the physical qualities of painterly light, in a way that can be seen on the same axis along which I have positioned Flavin and Olitski.

As with pointillist ways of working with color, another important 19th Century innovation regarding light is the photograph; which, at least via the photosensitive chemical processes it historically relied on, renders light an active agent in the generation of an image. We can see this in Wolfgang Tillmans’s abstract photographs, where the process of photographic development gives rise to a luminous image that is only referential to that process by which it was generated.

The younger artists in the exhibition work from these various positions, updating them for the present. For example Jean-Baptiste Bernadet’s neo-pointillist color fields that change when illuminated differently. Similarly, other artists like Svenja Deininger and Philipp Rößle also work in more traditional means, such as painting and watercolor but, consciously or not, have absorbed digital ways of reading the image, by confusing the arrangement of figure and ground via scraped versus layered paint in Deininger, and the physical addition of the disambiguated glass prop in the case of Rößle.

In different ways, Guilia Cenci and Aaron Bobrow use commercial plastics to introduce a luminous play of light scintillating over and within otherwise minimal surfaces; referencing, in the case of Cenci, Flavin’s material intervention into space, and in Bobrow’s, Cane’s opening up of painting to the wall on which it is hung. Oliver Laric builds up vibrant fields of holograms, which are generated by an exacting photographic technology; buying those used in credit cards, passports, and other documents requiring authentication direct from the factories, mostly in China, that produce them. This extends a formal conversation to a political one involving the global circulation of bodies, currency, and goods. Tying together several strands of the exhibition Robert Sandler collapses the photographic into the painterly by producing and displaying paintings on the iPad. Here technologized light becomes both formal substrate and means of display.

Lumination reveals that as long as technology continues to adapt to, and update our understanding and experience of light, so too will artists track those aspects of light as they pursue the various meanings and ends that light takes on in contemporary society and culture.

Alex Bacon