The Surrogate

-

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Stabat Mater, Pathosformel 1,2023

Oil on cotton

165 x 123 cm -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Stabat Mater, Pathosformel 2,2023

Oil on cotton

165 x 123 cm -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Stabat Mater, Pathosformel 3,2023

Oil on cotton

165 x 123 cm -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Stabat Mater, Pathosformel 5,2023

Oil on cotton

160 x 120 cm -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Stabat Mater, Pathosformel 6,2023

Oil on linen

165 x 123 cm -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Stabat Mater, Pathosformel 7,2023

Oil on linen

165 x 123 cm -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Stabat Mater, Pathosformel 8,2023

Oil on linen

165 x 123 cm -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Stabat Mater, Pathosformel 9,2023

Oil on cotton

160 x 120 cm -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Stabat Mater, Pathosformel 10 (after Michelangelo),2023

Oil on cotton

165 x 125 cm -

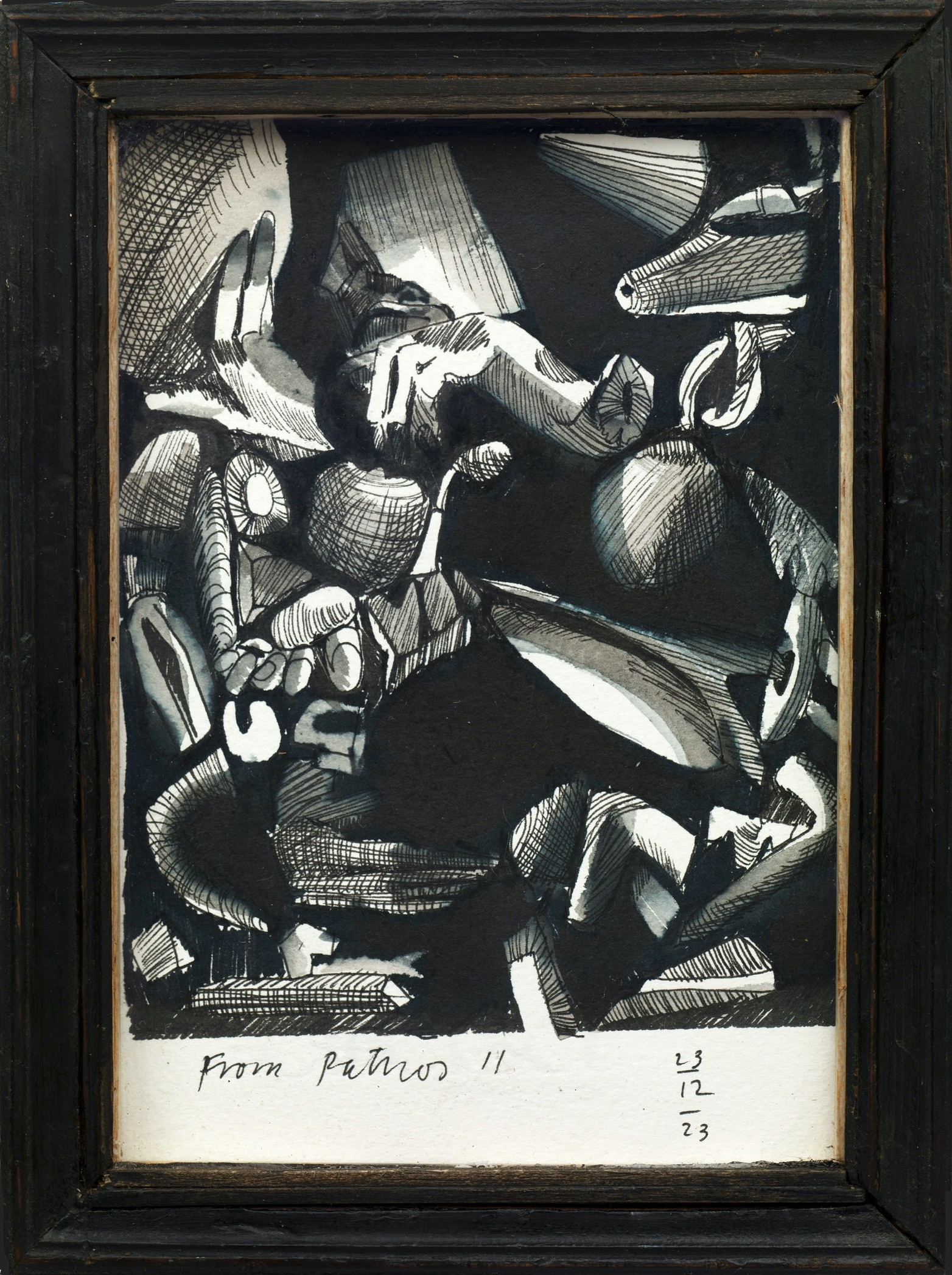

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Stabat Mater, Pathosformel 11, 2023

Oil on cotton

165 x 125 cm -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Porcelain Agnus Dei,2022

Oil on linen

25 x 37 cm -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Study for Stabat Mater Pathosformel,2023

Ink on paper

18 x 13 cm (framed size) -

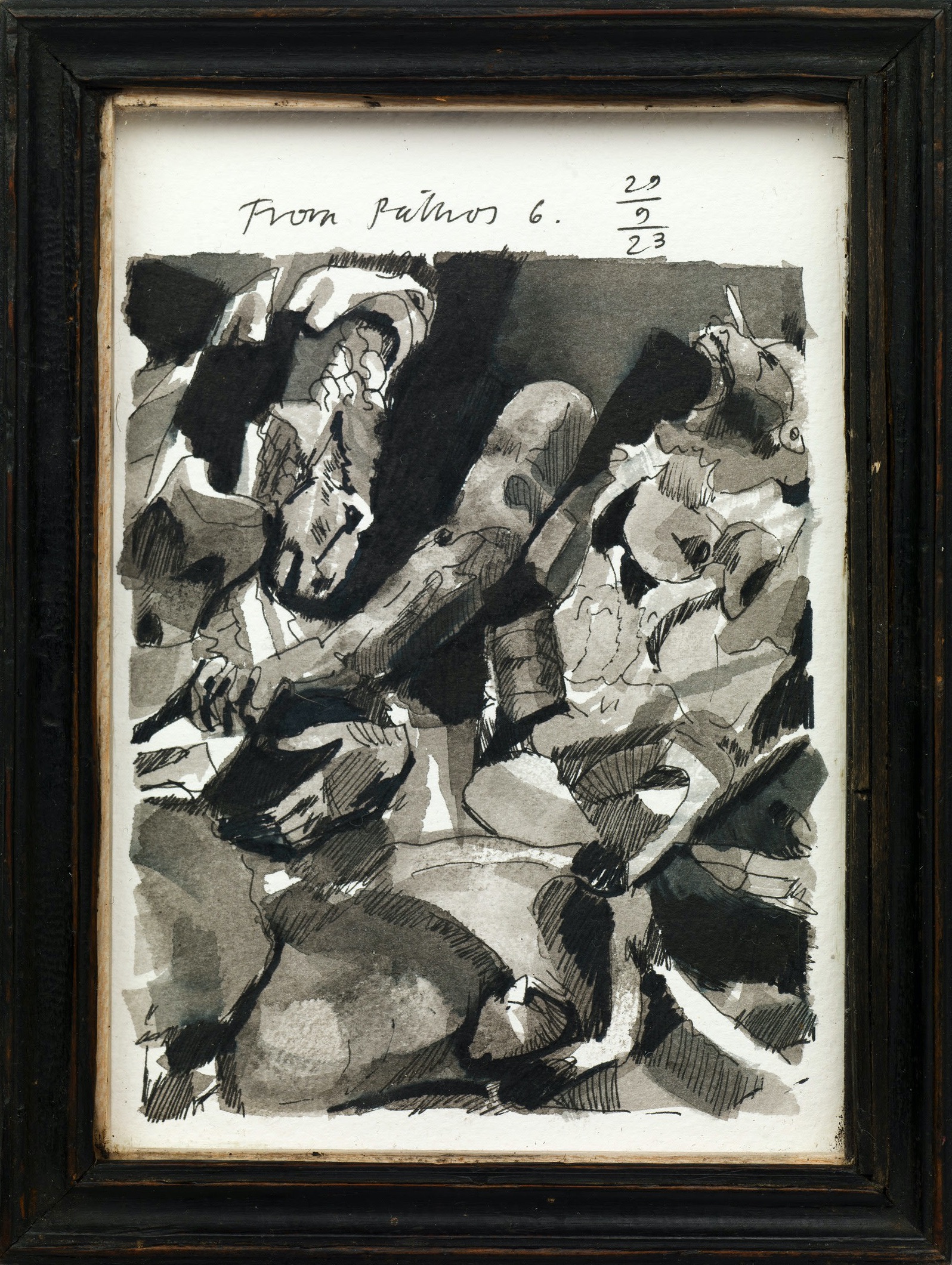

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Study for Stabat Mater Pathosformel,2023

Ink on paper

18 x 13 cm (framed size) -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Study for Stabat Mater Pathosformel,2023

Ink on paper

18 x 13 cm (framed size) -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Study for Stabat Mater Pathosformel,2023

Ink on paper

18 x 13 cm (framed size) -

![]() W. K. Lyhne

W. K. Lyhne

Study for Stabat Mater Pathosformel,2023

Ink on paper

18 x 13 cm (framed size)

W.K. Lyhne, The Surrogate at Patricia Low Contemporary

By Emily Steer

W.K. Lyhne’s guttural paintings seem to emit a mighty yet silent scream. Muscular human limbs, ewes’ ripe pink bellies, and hybrid human-animal faces are depicted in a ferocious tangle. Each part appears disembodied but ultimately connected to the forms around it, as though comprising one single creature. These brawny beasts are mostly contained within deep, bloody red and black backgrounds, which evoke both the dark bowels of human- made spaces and the insides of the body. Wet paint is pulled through viscerally, in thick, sensual strokes. A raw, emotional cry is threaded between all the paintings, with the artist drawing parallels between the repressed maternal grief of the Virgin Mary and the urgent call of ewes for their young.

Each work is named after the Stabat Mater: a 13th-century hymn that reimagines Mary’s suffering at the death of her son in song and therefore sound form. The works explore the traditionally Western visualisation of female rage and pain. The Christian great mother, cut off from her sexual and bodily urges as a woman, is often shown as pure, demure, and lacking the feelings that make all humans animal. Her body is used as a surrogate for God’s child, and she is elevated above mortal feelings and desires. Popular images of Mary holding or mourning Jesus often highlight a moment of serenity and beauty in her sorrow, perhaps with a single tear or a refined, doleful expression. What of the frenzied, gutted, despairing woman who has lost her child?

Lyhne finds kinship between this sanitized treatment of Mary and the plight of ewes, many of whom experience a life of industrialised motherhood through the farming and wool industries. These animals are also often artificially impregnated, acting as surrogates of their money-making young who will ultimately be taken away from them. As their bodies are used over and over, their fate is to repeatedly suffer the loss of their lambs.

The artist has been particularly interested by the desperate calls between ewes and their young when the mothers return from shearing. At this time, the lambs no longer recognise the ewes, and the cacophony of panicked calls block the mothers from hearing their individual child’s cries too. It is this urgent scream that pierces through The Surrogate’s paintings. The body becomes expressed through feverish emotion and movement, no longer a solid, tangible form, but a frenetic knot of energy. Hands and arms contain, hold and press, while breasts and bellies expose and seduce. Lyhne’s mothers are complex and nuanced: human and animal; loving and sexual; pained and pleasured. Their bodies are also inherently connected with their children.

The ewe is shown in parts. In some works, her face screams as her eyes and tongue seem to pop out. In others, she takes on the role of the Annunciation’s angels in the top corner of the canvas. Her swollen stomach is shown stretched and bulging. Her hoofed foot sticks up at ungodly angles. She is depicted as soft animal, nurturing mother, and exposed meat. Lyhne’s paintings convey the economic role of the ewe from pre-Renaissance times to now, in which sheep are bred for profit, their bodies enabling power and finances to grow as their

bodies are stuck in a loop of expansion, expulsion and contraction. She becomes the archetypal mother, a pliable body used for birthing and money-making.

As for Mary, Lyhne removes the often-singular focus on Jesus’ endurance, instead highlighting the physical pain of birthing, carrying and loving her child, followed by the emotional agony of losing him. The artist reconnects Mary with her animal, fleshy body, free from the restraints of purity and saintliness. In some works, a pair of firm, bare breasts puncture a cluster of hooves, hands and feet, in reference to the lack of historical breastfeeding images of Mary; a natural act deemed too impure and animal for her in later Christian iconography.

The paintings also combine an energetic selection of art historical references, with rich Baroque colouring; nods to Holbein’s skull; and the repeated inclusion of Jesus’ muscular but broken arm from Michelangelo’s The Deposition (also called the Bandini Pietà, 1555). As such, they seem to exist outside of time, evoking not a particular past or present, but an ongoing, eternal scream emitted from aching female bodies. Walking through The Surrogate, the paintings evolve from entangled compositions in the middle of the canvas, to sprawling vortexes that the viewer might feel as though they are falling into.

Each work is a painterly attempt at a pathos formula; a single image created to arouse a powerful emotional moment. The feeling conjured by the work could be seen as pre- linguistic . Many of the limbs, torsos and heads that tussle and twist on the canvas cast long shadows over other parts. These shadows speak of intangible states existing beyond words, which are best expressed with a wretched, aching scream.

Lyhne, in committing these ideas to canvas, opens her imagination to the viewer. As such her paintings are more than simple translations of the external world. This is important because what emerges from these exploratory forays into imagination – is the ability to revive the image – which if it were not, risks the world of Mary perishing and perhaps dying from its perceived completeness. With all that in mind, enter the exhibition with your own sense of openness and in doing so see where your imagination takes you.

W.K. Lyhne is a London-based contemporary artist. Her recent work draws parallels between the urgent cries of ewes when separated from their lambs and subdued popular depictions of the Virgin Mary in her grief at Jesus’ death as well as a contemplation of what motherhood is given to hold . Lyhne is currently completing a practice-based PhD with supervisors from Chelsea College of Arts, UAL and the University of Oxford, exploring the connections between maternal behaviour in animals and humans. Her work has recently been exhibited at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool (2023); TJ Boulting, Lungley and Hales galleries in London (2022); and Athens’ The British School (2022). She is the co-founder of the Sequested Art Prize, awarded for self-portraits created in the home and supported by the Arts Council Heritage Lottery Fund.

Emily Steer is a London-based art and culture journalist. She has written for titles including BBC Culture, the Financial Times, Frieze, Harper’s Bazaar, and Wallpaper. Her writing often explores the intersection of art and mental health, informed by her psychodynamic psychotherapy training.